Automated Level Placement: Are we there yet?

A good level placement test should be efficient and reliable. Having hundreds of students line up for an interview with one of your English teachers may be reliable, but it is unlikely to be an efficient use of everybody’s time. In contrast, a multiple choice test may seem efficient because of automated scoring, but if the test recommends the wrong level because it measures memorized facts instead of communication skills, then it can hardly be considered reliable. Teachers like me want an online test that measures all four language skills plus interaction and arrives at the same level placement recommendation as expert teachers would make.

Our college doesn’t have a very good online level placement test, so all members of my department have to scramble to check each student’s level during the first week of classes. With 30-38 students per class, only two hours of class time, and one short hour in the computer lab, we teachers usually feel rushed and overloaded. So, I have been interested in developing innovative new automatic evaluation tools for years now. This article is about those tools.

What about the grant?

Some of you might ask, wasn’t there an ECQ grant to develop a free level placement test? Yes, there was. But that’s gone. To make a long story short, I applied for an ECQ grant to develop a test in 2021. Intent on full disclosure and transparency, I wrote in the grant application that half of the grant money would be used to hire my company and my team of web-developers to develop the testing technology. The grant was approved, but then our college contract lawyer put a stop to the project. My college was forced to cancel the project and return the unspent money.

Why? Public institutions cannot funnel money to an employee’s company, no matter how good the cause or how much of a bargain can be had by doing so. It’s considered a conflict of interest. I’m an employee of my public college. My publishing company is ineligible to receive a contract. So no money came from the grant to develop any automated evaluation tools.

Nevertheless, I was able to get release time (one course off) along with Rachel Tunnicliffe and Tom Welham at Merici College to do the research and develop some interesting testing ideas. We did a lot of work, got some layouts made, and the money was well-spent. Teachers own the copyright of all their efforts, so those ideas are not lost.

You should know by now that I don’t give up easily, so I have focused on developing VirtualWritingTutor.com and Labodanglais.com with money from my own pocket. Bad luck won’t stop us. It just slows us down, right?

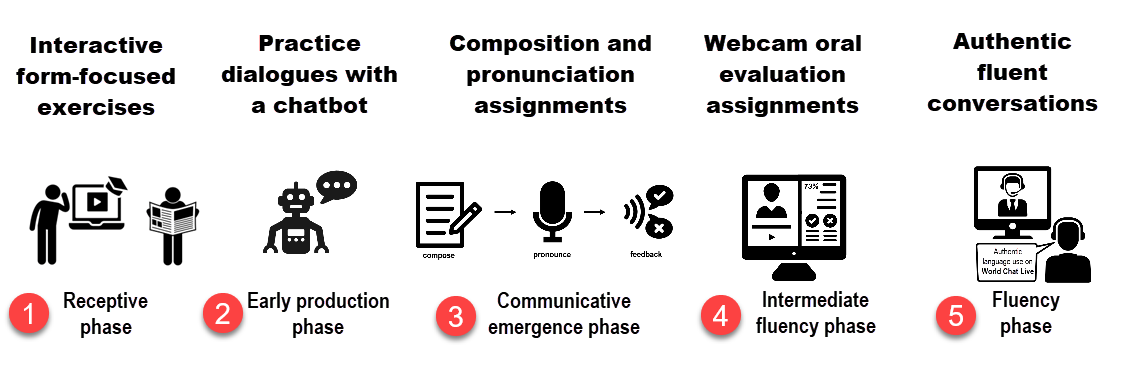

But this article is not about the recent legal drama at my college, it is about the suite of tools I have managed to develop for Labodanglais.com. If the tools work as expected, they will get us closer to the goal of a reliable, web-based, free, level placement test for college students here in Quebec–albeit in a roundabout way. They also have some interesting implications for using the 5 phases of Skill Acquisition Theory (Dekeyser, 2007) in college ESL courses.

Here’s what we have so far.

Self-assessment affirmations

Who knows you best? You do, right? So why not simply ask students how good they are at English? Self-assessment has the potential to make short work of level placement.

If you are familiar with the CEFR, you know that the Common European Framework of Reference defines their levels of proficiency without referring to grammar. Why? European languages do not share the same grammatical features, so it is impossible to describe proficiency for all languages by checking off a list of the grammar points mastered. Instead, the CEFR defines their 6 levels of proficiency in terms of what the learner can do. In this way, students of foreign languages (and their employers and their teachers) can quickly get a sense of the student’s proficiency level by checking off a series of can-do statements. Smart, right?

Labodanglais.com provides teachers with a quiz containing a series of videos with can-do statements. Students watch the videos and select the statement that matches their self-assessed level. The voices were generated using Speechelo. The animations were generated using Toonly. Here is an example of a video with a can-do statement that matches the B2 (102) level of listening comprehension.

There are 4 skills (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) to self-assess using this quiz plus interaction, making a total of 5 skills. Each skill has 5 levels of proficiency in the case of junior colleges in Quebec (A1-C1). That equals 25 videos to watch and totals about 8 minutes of video watching.

Is this an efficient use of time?

If it works reliably every time, 8 minutes is not too bad. Still, a colleague once told me that a skilled teacher only needs 2 minutes one-on-one to place a student. That’s the gold standard we should always remember while discussing automated evaluation.

Students are not always honest on self-assessments, and they sometimes claim (and often believe) that they are better or worse than they actually are. Self-assessed affirmations are not 100% reliable. An objective evaluation of proficiency is also needed to balance out subjective self-assessments. Read on for more.

Pronunciation quizzes

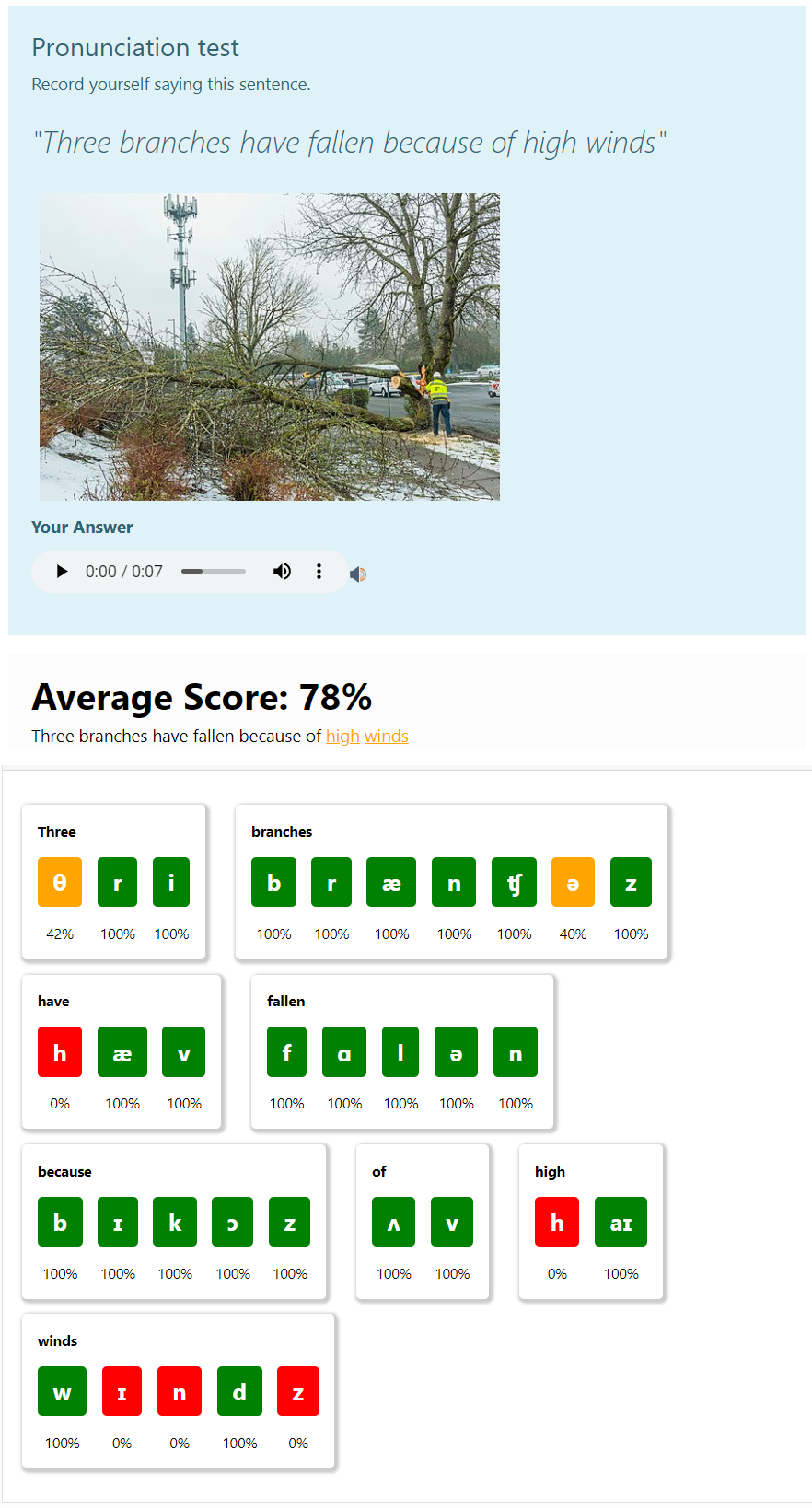

With the help of our team of expert Moodle developers, we have developed an automated pronunciation quiz plugin for Labodanglais.com. It can distinguish between high and low scoring pronunciation, but (to be honest) the scores and feedback are not easy to interpret. Ambient noise and low-quality microphones affect the accuracy of the scoring. Furthermore, learners who get started learning English later in life will have a stronger accent than those who learned it during the sensitive period of childhood despite excellent communication skills. Level placement decisions are complex.

Here is my simulated accented voice recording made with the integrated microphone on my laptop. Notice I said “tree” instead of “three” and “branch” instead of “branches. I dropped the “h” in “have” and “high.” Also, I mispronounced the vowel in “wind” which should sound like the vowel in “win.” Instead, I said “wind” with the same vowel as “wine.” The pronunciation is correct in some contexts but not this one.

The system scored my pronunciation of this one question (there are 5) at 78%, but what proficiency level does 78% indicate? A2? B1? Averaging the scores of all the words in a sentence seems fair, but in our context here in Quebec, the missing -s, missing h- and the incorrect vowel pronunciation of “wind” are the only scores that matter to me. An intelligent pronunciation test needs to focus on targets within a meaningful context–not averages. An automatically generated score is nice, but what does 78% mean in terms of level placement? I need to work out thresholds and other measures of proficiency. Moreover, I will need more student data.

Vocabulary

According to EnglishProfile.org, students at higher proficiency levels predictably use certain topic-related vocabulary that students at lower proficiency levels will never use. One topic that seemed universally accessible and a perennial challenge for lower-level students to Rachel, Tom, and me is body parts. Using icons to represent the body parts seems a reliable way of eliciting target vocabulary without requiring students to do a lot of reading and head-scratching. (Attention is a limited resource. Long texts wear out easily distracted students.) So, we came up with a quiz that randomly selects body-part vocabulary from a series of graded question bank categories with icons.

Here’s what the vocabulary quiz looks like. There are10 randomly-selected questions each time the quiz loads. What level would you put a student in if they knew these words?

Will this test discriminate between the levels as well as we hope it will? I will be able to tell you what I discover in a few weeks.

Oral proficiency evaluation

If you have been following Labo News, you will know all about how our team of developers has created a webcam oral evaluation plugin for Labodanglais.com . Automated oral evaluations can be used for oral practice within the context of a course, and they seem like a great way to provide frequent feedback on content and grammar to students while they practice. It also seem possible to use webcam evaluations at the beginning of the semester for oral proficiency evaluation tests. This will be the first semester Labo teachers will have access to this feature. We’re pretty excited!

I created three proficiency tests over the summer:

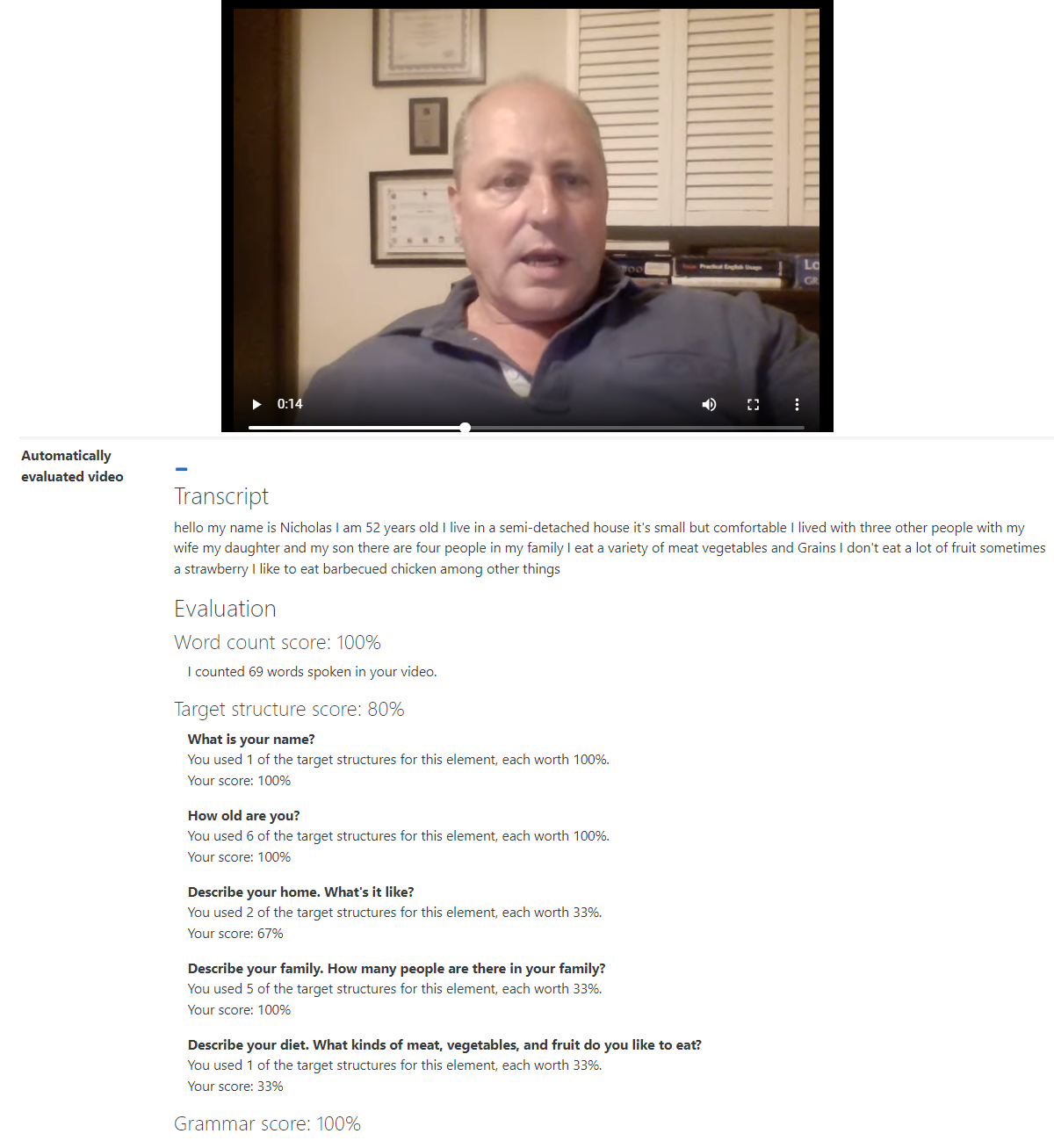

- The first asks students to answer questions about their name, age, home, family, and food preferences. It seems relevant to 100 (A2) students.

- The second does all that and asks students to talk about their summer to evaluate their past tense verb knowledge. It seems relevant to 101 (B1) students who must use verbs in reference to the past in their final college oral evaluations.

- The third asks students to talk about the value of education, checking for a range of topic-related vocabulary and the number of common verbs used. It seems relevant to 102 (A2) students who must learn enough topic-related vocabulary to express clear and coherent arguments by the end of the semester.

How does it work?

The student records a video with their webcam. The system then extracts the audio file, converts it to text, counts the number of words, checks for target phrases, and checks for errors. The assumption is that more proficient students will speak more words, use more topic-related phrases and vocabulary, and make fewer errors. The technology that we have developed is still in its early stages in the sense that we are only scoring the number of words, the number of topic-related word matches, and the number of errors. A human listens for meaning. Robots can’t.

In the example below, you can see how Google’s speech recognizer adds no punctuation and seemingly capitalizes at random. So what? So, we had to turn off all of the grammar checker rules that dealt with spelling, punctuation, and capitalization on VirtualWritingTutor.com when we send the text to it for a grammar check. The VWT uses sentence boundaries to determine what the subject of a sentence is, what tense the verb should be, and if two words belong together or not. We are still learning about the limitations of the current implementation of this error detection system. Nevertheless, I feel optimistic that we can get some meaningful scores with what we have so far.

Here’s how the feedback and score look. That’s a screenshot of me speaking into my webcam. Below my face is the transcript of what I said, the target structure score, and the grammar score. I notice now that I said “a strawberry” but my list of target structures (not shown) only had the plural form “strawberries” in it, and so I didn’t get full points. To be clear, that’s not a problem with the technology but with my implementation of it. My list of targets was incomplete. This is one reason why test items and procedures need piloting and debugging. I am eager to see how the system will evaluate students so that I can debug it further.

I am also eager to see how much it costs. Google charges $0.03 USD per minute of speech recognition. If every one of the 1500 students using Labo this semester speaks for 3 minutes, that will cost $145 USD. If it works, it’ll be worth it. If it doesn’t, it’ll be another expensive lesson learned.

Writing evaluation

In the context of a course, it makes a lot of sense to give students automated feedback on the word count, the structure and content of the essay, and on common grammar errors. The feedback is fast and for the most part reliable. It is still far from perfect. In the context of a proficiency test, students don’t get any time to plan, research, and revise their essays. These difficult conditions make scoring a text for proficiency challenging. You will see why below.

I have developed two writing evaluations that seem relevant.

- An email task for beginners and low intermediates (A2, B1)

- An essay writing task on the value of education for high intermediates and advanced learners (B2, C1).

Email writing task

Here are the instructions for the email writing task. Notice there is no indication about the structure of the text. The system will evaluate the use of salutations, introductions, topic-related vocabulary, and closings, topic-related vocabulary, and grammar. Will the Instagram generation of students know anything about the conventions of email writing? Some will. Some won’t. Is it relevant? Dunno.

Try it on the Virtual Writing Tutor grammar checker here if you get the chance.

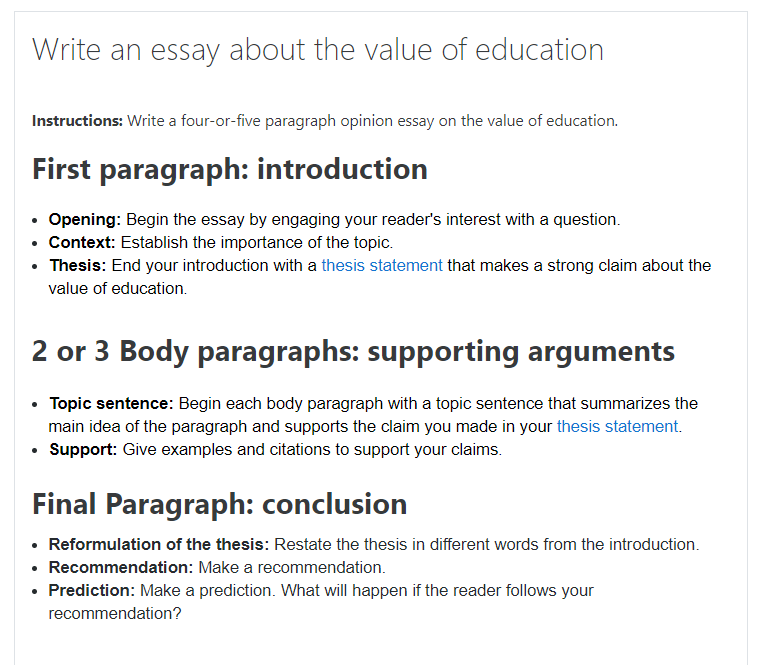

Essay writing task

Here are the instructions for the essay writing task. I thought it wise to include some. The system will evaluate the length, use of introduction elements, thesis sentence strength, topic-sentence strength, paragraph development, conclusion elements, vocabulary, and grammar. In part the system is evaluating the student’s ability to follow instructions. Try it on the Virtual Writing Tutor here.

I’m not sure how useful these evaluations will be. There is no real incentive for students to do their best on level placement test in the current CEGEP ESL system. Students don’t always want to be in the correct level. Some students think that lower level courses will be easier than higher level courses. They believe it is better to be in a lower level and get bored rather than be placed in a higher level and make an effort. For myself, I can’t think of anything worse than being bored, can you?

There are other concerns. What if you have a native speaking student who has no strong opinions and writes very little? What if an eccentric student tries to show you how creative and clever he or she is by writing the essay in rhyming couplets? Reticence and brilliant non-conformism will score lower using the current automated evaluation tools we have at our disposal. Obviously, we will be watching to see how reliable this and the other evaluations will be.

Getting closer

The dream of offering an effective 4-skills level placement test to all colleges has progressed to this stage–we can now offer a level check through a pay-for-use Moodle website using automated evaluations. The loss of ECQ funding to develop a full-blown level placement test was a disappointment to be sure, but I’m not ready to give up. Indeed, these kinds of preliminary pilot tests each semester bring us ever closer to our goal of an intelligent learning management system.

In time, we will be able to answer the question, “Can this tool provide a valid measure of proficiency for our target population? Is this tool-and-task combination reliable considering the seemingly chaotic nature of creative language use?” Hopefully, I will be able to say, “Yes.”

We should also ask, “How much human supervision is this robot going to need?” Hopefully, I will eventually be able to say, “None.”

In the interim, testing and developing these automated scoring tools can provide us with a definitive answer to the perennial question from disengaged students in our classrooms, “Is this activity important? Does it count?” A reliable automated scoring system will allow us to say, “Yes, it counts. Do your best.”

Skill Acquisition Theory (Dekeyser, 2007) teaches us that practice matters. Experience teaches us that if it doesn’t count, some students won’t do it and they won’t learn the skill. So, make it count, teachers. Automate scores! Let the student know their efforts are being tracked–and rewarded.

A word of thanks

The teachers who choose to use Labodanglais.com with their students are indirectly helping to fund this research. I’m very grateful to them for this support. You can imagine how expensive these tools are to develop on my college teacher’s salary, all the while gobbling up a lot of time during my summers, evenings, and weekends. Developing these tools seems absolutely worthwhile, nonetheless. I am committed to making a non-trivial difference in my field. Furthermore, the feedback teachers provide is enormously helpful and deserves to be rewarded with better evaluation tools. Their support has been making a difference. Thanks, Labo teachers!

What’s next?

We are working on detecting proficiency levels using part-of-speech tags and vocabulary lists. Some words are easy to score in terms of A1-C2 proficiency. Health related words like “longevity” and “joint pain” will only be used by advanced learners. “However, other words are more difficult to score automatically. For example, the word “water” is a very common word when used as a noun to mean the liquid. All beginners can use “water” in that sense. But only high intermediates use water as a verb in the sense of watering the flowers. Even more impressive is when a student uses “water” in the sense of causing salivation. Only advanced learners use “water” as a verb to say that an aroma makes their mouths water.

There are thousands of separable phrase patterns in English like “make(s)/made/making” + “my/your/her/Ramsay’s cooking” + “mouth(s)” + “water” that we could define using a computer language like Regex. As you can see, there are conjugations of the verb (makes, made) that need to be accounted for and singular/plural inflections of the noun “mouth(s)” in addition to the separability of these elements to allow an infinite variety of possessive forms and names in-between: made my mouth water, making our mouths water, makes British chef Gordon Ramsay’s mouth water, etc.

My development team and I are therefore currently working every spare moment on new methods to detect the level of a learner’s English using computerized natural language processing techniques. It will be achievable eventually–by not only detecting what words the learner uses–but also by detecting the part of speech and the linguistic context of how he or she uses them. The range and complexity of these grammar rules is astounding. You have to admire the speed and processing power of the fluent second language speaker’s brain which recognizes patterns like “make my mouth water” so effortlessly. Computerized methods are so clumsy in comparison.

Once these patterns are defined, the next step will be to find tasks that elicit these complex phrases without direct and explicit prompting. We want to trigger the learner’s most advanced language structures without resorting to long paragraphs of explanation or translation questions that won’t be completed automatically using a phone’s translation app. Challenging, right?

Another goal is to develop an automated evaluation of each student’s ability to interact n the second language. I have developed a system that generates chatbot dialogues, but it doesn’t score them. That’s next on my to-do list.

The work continues. I hope you will join us. Contact BokomaruPublications@gmail.com when you are ready to give these tools a try with your students.

Reference

Dekeyser, R. (2007b). Skill acquisition theory. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 97-113). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.