Letters to the House of Commons

Teachers often talk about helping students become good citizens. But how can this be achieved in a practical sense? How about repurposing the argument essay discourse model they learn in Actively Engaged in Persuasion and write a letter to the House of Commons in Ottawa?

Method

During the semester, my 102A students at Ahuntsic College and Helen Hefter’s students at Montmorency College wrote and revised argument essays on each of the 6 topics in the course: a fast-food tax, internet censorship, animal rights, abortion, feminism, and body image. For our final evaluation, we asked students to write an argument essay on climate change in the form of a letter to Parliament.

Materials

Here’s how we set it up. We gave students the following materials during week 14. Teachers, you are welcome to use and share these resources in any way you like.

- an article on the climate crisis

- flashcards with climate change vocabulary

- instructions on how to outline and format a letter

- an envelope

- an address label

- a PowerPoint explaining the House of Commons Letter with a speed review game

Learning to write an argument essay has pedagogical value. Students grapple with controversies, learn vocabulary, ask questions, describe the impact of a problem, make strong claims, quote, provide support from their research, make concessions and refutations, paraphrase, and make calls to action and predictions.

However, we reasoned that writing an final essay that only a teacher would “read” and then score is pretty pointless in a practical sense, but sending a handwritten letter to a politician in a democracy has real-world value.

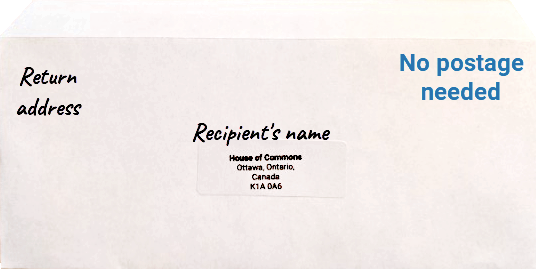

Students had a choice to put their letter in an envelope with their return address or not. If they did, it meant they wanted us to mail it after scoring it. If they handed in their letter without an envelope, it meant that they didn’t want us to mail it.

Results

We each had two groups of 102s at our two colleges, totalling about 120 students. Combined, there were 57 handwritten letters in envelopes with 31 written by Ahuntsic students and 26 written by Montmorency students. My groups were larger, so Helen had a slightly better participation rate.

They should arrive on Justin Trudeau’s desk tomorrow.

Discussion

Both Helen and I observed a few unexpected things about our students. Most students didn’t know that you can send a letter (without a stamp) to members of parliament. Most students didn’t know how to address an envelope. Most students were unaware that a letter should have a return address on the outside of the envelope for the post office (just in case) and a return address at the top of the letter so that the recipient would know where to reply.

The salutation and closing were a problem for some. The capitalization and punctuation conventions of the salutation on its own line were new for many of them. Only poetry and letters end a line with a comma (“Dear Justin Trudeau,”). The “close” also posed problems for some, with one student closing his letter with “Regardless,” instead of “Regards.” ![]()

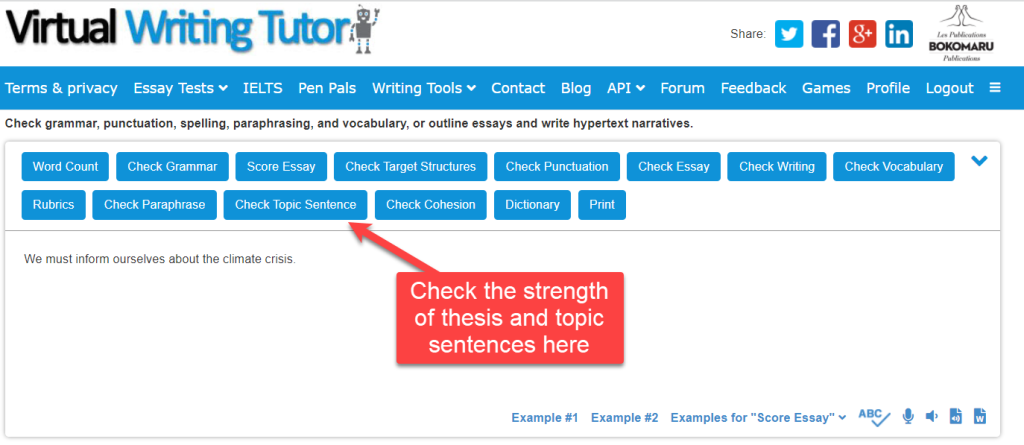

Writing an argument essay was not difficult for most of them. The structure and purpose of the writing task were clear for most students because they had had so much practice during the preceding weeks with Labodanglais’s automated essay evaluation system.

Even so, a small minority with poor attendance had trouble with the purpose of the letter: to persuade the government to take immediate action. Instead, one or two wrote thesis statements like this: We must inform ourselves about the climate crisis. Obviously, this is a rather weak call for action.

Also, some students failed to understand their audience (in this case Justin Trudeau), opening their essay/letter by asking questions like, “Do you know that the planet is warming due to our use of fossil fuels?” It is an absurd and insulting question to ask an educated reader who had just returned from Cop26. Justin Trudeau knows about the causes of climate change.

Only about half of the students opted to send their letters. Half did not. I asked students who opted out why not, and I got three answers which I will paraphrase for you here:

- Justin Trudeau won’t read it, so there’s no point–it’s an exercise in futility.

- I don’t want Justin Trudeau to think less of me for having bad grammar.

- There are no extra points or immediate advantage for me.

These comments came as a reminder that students come to us with ideas and attitudes they learned elsewhere. Perhaps students need to learn about successful letter writing campaigns in the past to give them courage. Perhaps, an overemphasis on error correction is making them self-conscious. Perhaps the overemphasis on grades is giving our students tunnel vision. I can’t say. In any case, learning good ideas means unlearning bad ideas. It’s is something to think about.

Conclusion

Despite the difficulties students faced, we believe the project was worthwhile. Showing students how to use the communication skills they learn in their English class to perform real-world tasks is an important step for ensuring a transfer of learning.

Aside from that, we are facing an existential crisis. Education cannot just be about the transfer of inert information. It has got to empower people to take action. Otherwise universal education is a distraction from–rather than a fulfillment of–democratic ideals. This activity helped half of our students make the leap from knowing to doing.

Helen and I will continue to try to help the all of our students actively engage.