Give Your ESL Course a Personality Test

People can take personality tests. So can ESL courses. Different courses emphasize different learning goals, and suit some students better than others. Does your course reflect your personality or does it have a personality of its own?

You have probably heard of the Briggs-Myers Test, right? Briggs-Myers has been around for a long time, and it’s pretty famous. The test helps you discover if you are primarily introverted or extroverted, sensing or intuitive, thinking or feeling, and judging or perceiving.

The self-taught personality theorists Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers progressively developed their theory of personality types over many years, culminating in the The Briggs Myers Type Indicator Handbook, published in 1944. And it all started when Briggs met her future son-in-law, remarking how different his personality was from others. Eventually, the mother and daughter team came up with 16 personality types.

I’m supposed to be an ENFP Champion. Indeed, I can be extroverted. I like concepts and possibilities. I like logic, but I emphasize values. And I like new new challenges. (The Briggs-Myers personality types are probably not valid or reliable, but they are fun.) You would think that all of my courses and textbooks would all reflect those dimensions of my personality, so why are my courses so different?

Do courses and textbooks have personalities?

They certainly do. Just as individuals’ personalities differ from each other, college courses differ from each other in style and substance–certainly when the same course is taught by two different teachers and hopefully when two courses are taught by the same teacher. Courses and textbooks can each have their own distinct personality.

And why shouldn’t they?

As long as students achieve the Ministry objectives, nobody should bemoan the diversity of experiences that a student encounters at college. Each course should be different, and we should celebrate diversity. Courses with different personalities will nurture students with their different personalities.

But how do courses differ from each other?

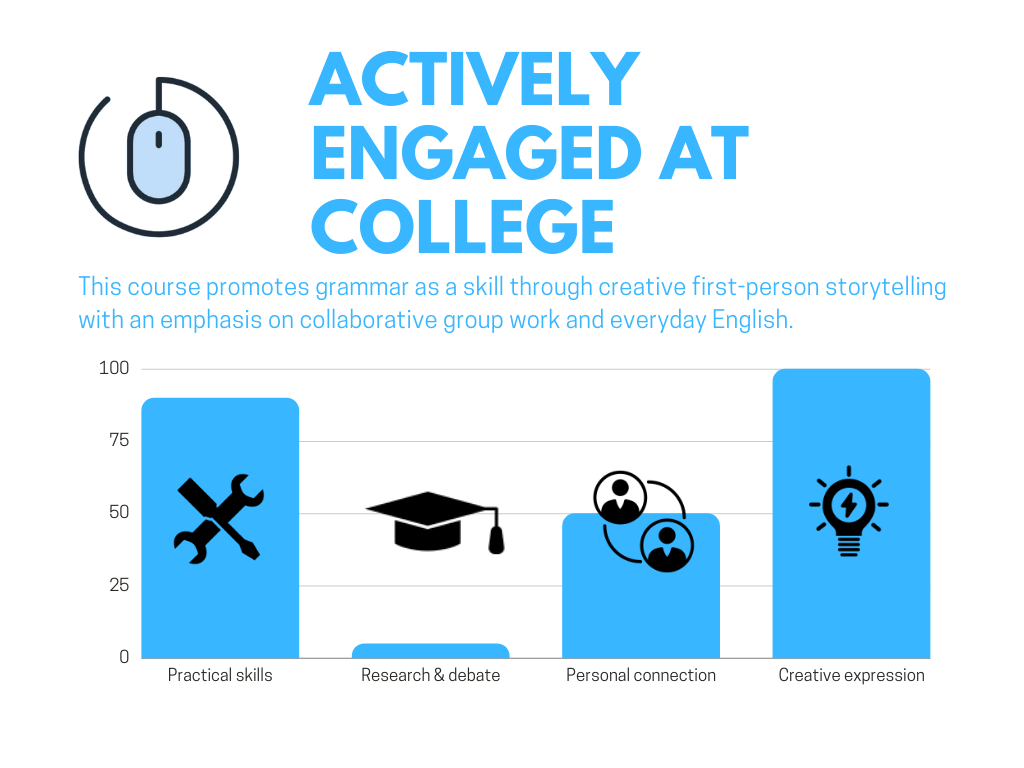

I have recently come to notice how my courses and textbooks differ along four dimensions: practical skill development, academic research and debate, sharing and caring, and creative self-expression. Each of these dimensions of a course’s personality represents four educational values. Do you share these values?

- College courses should be practical, focusing on measurable skills.

- College ESL courses should focus on academic discourse, especially with higher proficiency learners.

- College courses should promote sharing and caring, especially with beginners.

- College courses should promote creativity rather than analysis when fluency is the goal.

Don’t you agree that courses at different proficiency levels should have a different personality? I know I do. Take this test to find out where you stand.

Does your course have a practical skill orientation?

Does your course and textbook focus on practical skill development through focused structural practice? Your course is very practical when the grammatical structures must be used in the assignments or the final essay must have the exact structure studied in during the preceding lessons. If students are free to use or avoid the grammar from the course or modify the essay structure and still get a good score, it is less practical. Give your course a score for practical skills from zero to one hundred. How practical is your course?

Courses that score highly on this dimension emphasize mastery through repeated practice and feedback. If your students are encouraged to practice proscribed structures over and over again that they must use during the final evaluations to score points, your course has a practical skill orientation. If instead the structures you teach are not obligatory and students can receive a good score whether they use the structures taught in class or not, your course will score low on the practical skill dimension.

A course that emphasizes application is practical. A course that emphasizes exploration is less practical.

Some students don’t like a high degree of abstraction or open-ended questions. They don’t want to explore concepts and theorize freely. Instead, they want to learn what to do, how to do it, and when to demonstrate what they have learned. One student told me, “I don’t like philosophizing and fortune cookies. Give me skills I can use.”

The personality of every English course I teach stands in direct contrast to the courses I took as a college student. My teachers wanted big ideas from me–not target structures. They wanted me to explore and discover meaning.

I don’t like philosophizing and fortune cookies. Give me skills I can use.

Student

While I was at college, I remember my first year college professor asking the class to write an essay on Tom Sawyer. I liked the book, but had no idea what he meant by “essay.” Nobody had ever asked me to write an essay before. I didn’t know what to do. He did not explain.

When I handed in my composition and got my grade two weeks later, the teacher let me know that it was not what he was expecting. If I wanted to swim with the big fish, I would have to figure out how to write an acceptable essay fast without the benefit of any direct instruction from him.

That was the personality of education in those days. Practical structures were not taught. They were to be discovered. Sentence structures, paragraphing, and essay discourse models were to be internalized by reading important books and responding thoughtfully in writing. Exposure was believed to be enough to turn kids into scholars.

Teachers were, of course, reacting to Behaviorism. Students were not to be trained like rats in a maze. Thinking was more important. Cognitivist teachers believed that learning should focus on meaning not rehearsed behaviors.

In retrospect, schools had overreacted. Teachers had stopped teaching language as a structure with identifiable parts and purposes to communicate with people. We never talked about structure, purpose, or audience or our own writing. In those days, teachers were confident that structure, purpose, and audience would come to me if I would just read better books.

Reacting to their overreaction, I resolved early in my teaching career to focus on practical, step-by-step instruction. In my classroom, students gain practical communication skills developed through focused, meaningful practice. The argument you make or the story you tell can go in any direction, but you had better use the target structures we studied in class. In this situation, use this structure. In that context, use that structure. I teach target structures in obligatory contexts. I’ll give your context, and you supply structure if you want points.

In my 101A course, for example, every lesson has one or more target structures that students must practice. The repeated exchange of meaningful messages is a big component of learning in my courses. There are lots of error correction exercises, cloze listening tests, and grammar quizzes. Students encounter the same structures over and over again.

My goal is for students to leave my 101 course having learned grammar as a skill. I train them to use target structures in obligatory contexts. When you describe a scene, use “there.” When you say how an accident happened, use “when” and “while” with past tenses. When you complain about someone, use “X is always verb + ing.” When your regret, say “If only X had + past participle.” On the final exam, I give them the obligatory contexts: describe your house, tell me about the accident, complain about your roommate, and share your regrets. If they came to class and did the homework, I can simply count the targets. Practical, right?

Does your course have a research and debate orientation?

Does your course teach students to research and debate? Give your course a score on this dimension from zero to one hundred. Your course has an academic research and debate orientation if students do research to present other people’s ideas to prove a point. Alternatively, if your students speak and write to get to know and entertain their classmates, your course scores low on the academic research and debate dimension. How academic is your course?

Many of my colleagues teach academic skills to their beginners (100A) and low-intermediate (101A) students. I don’t. If students haven’t mastered the grammar of English, they should focus on composing narratives until they understand how verb tenses work. If you don’t know how to refer to what is happening, what happened, what will happen, and what could have happened had other things (not) happened, you should put opinion essays aside.

Storytelling is how we learn to express relationships of time and space in a language. Arguments can’t teach students about verb tenses. They show the relationship of ideas.

If however your grammar is pretty good, if you have good fluency, if you can strike up a conversation and communicate in everyday situations without difficulty, you should learn how to make a persuasive argument. Learning how to report what other people say in order to persuade your audience is the next step for you in your language education.

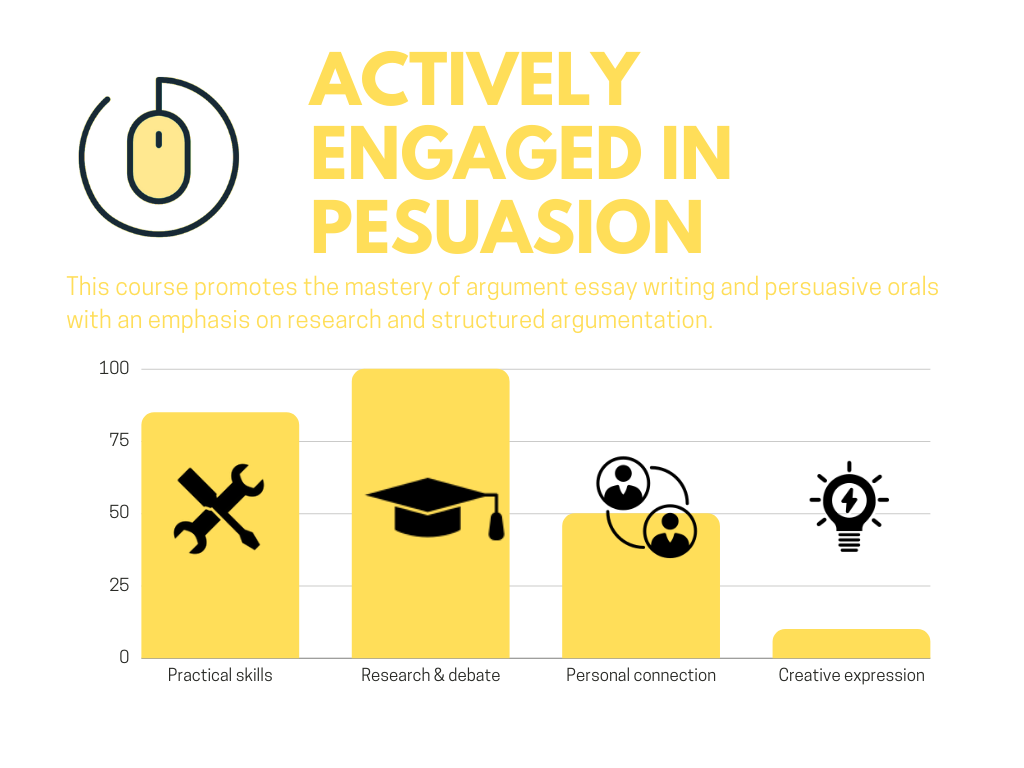

My 102A course has a completely different personality to to my 101 course. 102A is academic. Students must research both sides of a moral controversy, take a side and refute the opposing argument. There is a practical skill focus, but it is not about spatial and temporal grammar structures. Instead, I teach students larger structures; how engage a reader with a question, how to establish the importance of a topic, how to support a claim, how concede, and how to refute. I teach students how to sequence these structures in paragraphs. I teach a sequence paragraphs in a logical progression.

The obesity epidemic, internet censorship, animal rights, abortion, feminism, body image, who cares? Just tell me the answer.

Student

Some students struggle to formulate their own answer. They don’t have a point of view and don’t see why they need one. The obesity epidemic, internet censorship, animal rights, abortion, feminism, body image, who cares? Just tell me the answer. They want a practical structure that will get the job done, so they write thoughtless arguments like this: I am in favour of body image because… Or, they want to turn the argument essay into a report: There are arguments on both sides of this issue that I will explain to you.

Moral controversies stir no outrage in their souls. Censorship in China is fine. Women’s lack of access to abortions in Texas matters little. The personality of Actively Engaged in Persuasion course doesn’t match their own. These students would prefer storytelling. That’s ok, because that is coming next semester in Actively Engaged Online. It has a completely different personality.

Does your course have a personal connection orientation?

Does your course teach students to share and care? If it does, then that’s part of its personality. You can describe your course as having a personal connection orientation. Give your course a score on this dimension from zero to one hundred. How much sharing does your course promote?

Most teachers want their students to share. It’s in our speaking objects. Students must demonstrate openness and respect. At the heart of the communicative method is the idea of getting to knw each other through a meaningful exchange.

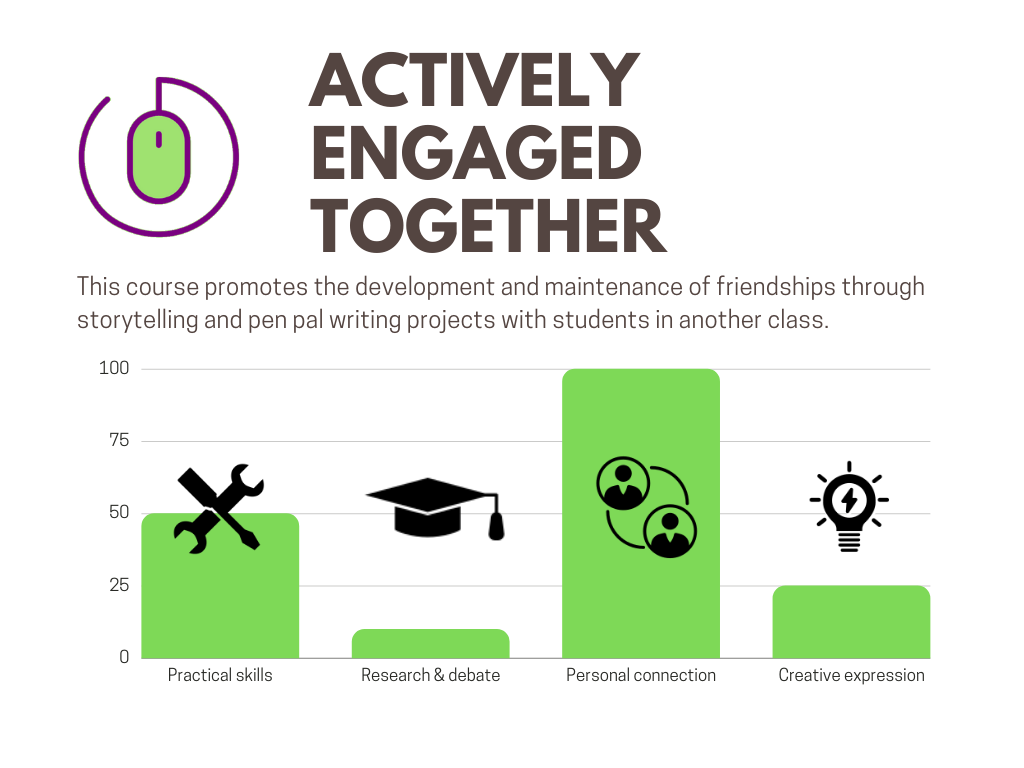

In my 100A course, I have students talk with each other in the classroom about their families, their neighbourhoods, the technology in their lives, food, a memorable day, or a memorable trip. In the lab, I get them to write pen pal messages to students in another class. Using English to connect with other people, to empathize, and to feel a part of a group can break beginners out of their monolingual isolation, opening a larger world to them.

But not everyone. Not all students want their ESL course to resemble group therapy. I ask students to share their contact information. Why? I have a boyfriend already. I ask them to talk about their favorite movies or music or sports or food. The answer does not always inspire caring and sharing in others when they say this: I watch reality TV in French, I only listen to what is playing on the radio, I watch hockey like everybody else, and I eat what my mother cooks for me. I’m not special.

I watch reality TV in French, I only listen to the radio, I watch hockey like everybody else, and I eat what my mother cooks for me. I’m not special.

Student

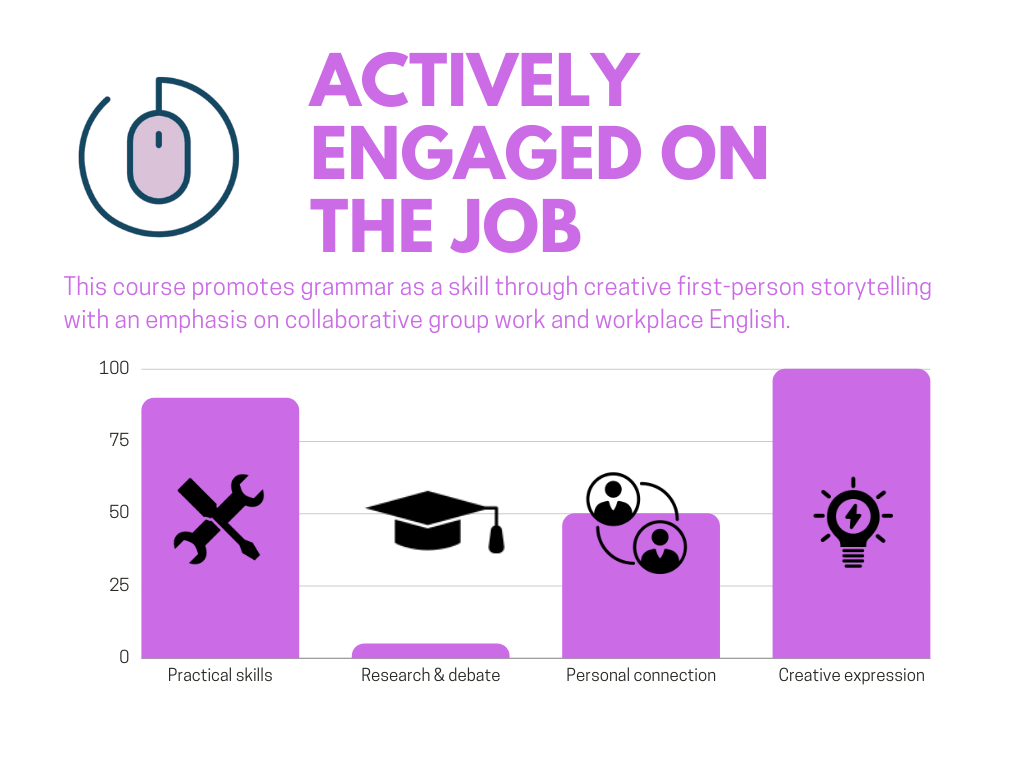

For a minority of students, the personality of Actively Engaged Together doesn’t match their own personality. That’s ok. Actively Engaged on the Job has a different personality altogether.

Does your course have a creative expression orientation?

Does your course teach students to use their imagination? If it does, then that’s part of its personality. You can describe your course as having a creative expression orientation. Give your course a score on this dimension from zero to one hundred. How much sharing does your course promote?

Many of my colleagues ask students to be serious, to understand, to argue, to describe, to report, and to persuade, but few ask students to invent stories. It doesn’t feel college level. But universities have creative writing departments, don’t they? Screenwriters workshop their ideas with other screenwriters, right? Every Monday, we try to find a better way to talk about our weekends when asked, “What did you do this weekend?” What could more practical than learning to tell a good story?

Students love inventing characters. They enjoy giving them lovable flaws. Students like being cruel to their inventions by giving them into dramatic encounters, disastrous days, tantrums, and love stories. They laugh at each other’s stories because they are designed to be funny, and laughter inspires them to collaborate further with their own suggestions, intensifying the conflict between characters. Adding creative storytelling to your ESL course will make teaching fun again.

In my 100B course, every lesson includes a game that encourages guessing and creative problem solving. And every lesson includes a new episode in a workplace story to invent and to entertain your classmates. Of course students must use words and phrases from their fields of study. But that comes easily.

Students imagine that each member of their group is an odd character in a shared workplace. Each student describes the workplace and his or her fictional character using first-person narration. Then, each student gives his or her characters a dream that reveal a desire or a fear for motivation, a bad day to add frustration, and workplace politics to navigate, a performance review interview to add tension, before the big layoff announcement and the crisis that ensues.

Students love the course. They love the drama. They love imagining their future careers, and they like the opportunity to be creative.

Do all of your courses have the same personality?

I certainly hope not. When your courses differ not only in content and goals but also in personality, teaching takes on a new level of fun that will keep your energy levels up year after year. When courses have different personalities, it means that students will eventually encounter a course course that matches their own learning preferences.

If your courses resemble each other in personality, try mixing things up with a new textbook.