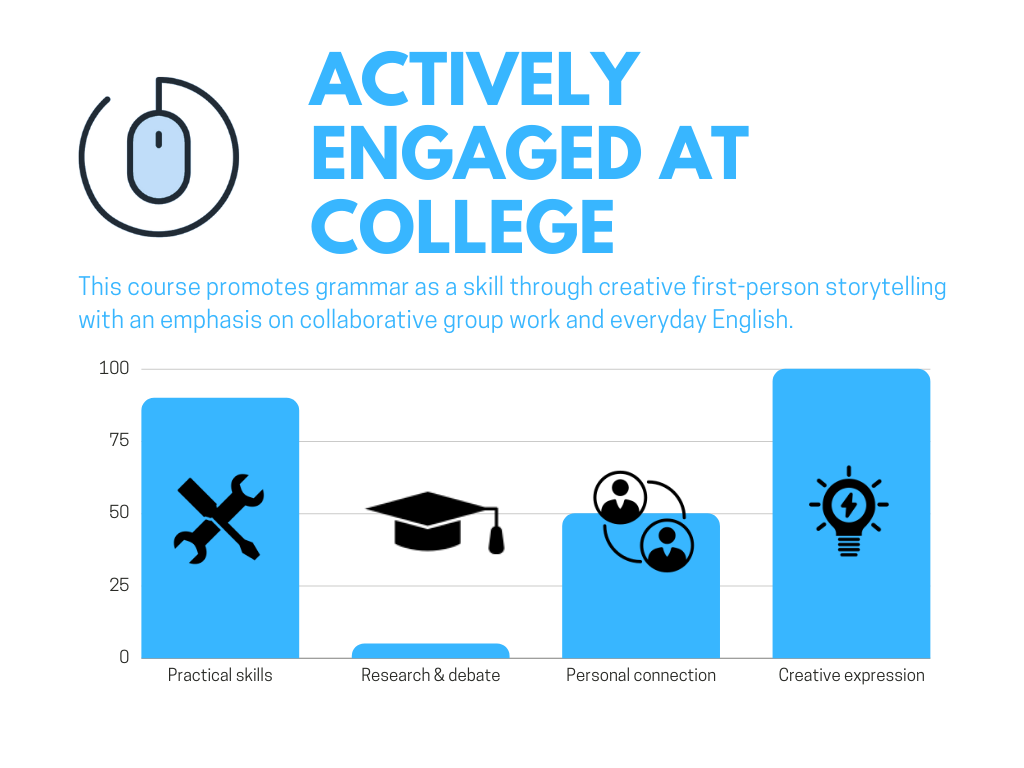

Actively Engaged at College

This ESL textbook is very different from other textbooks. It addresses the government objectives by encouraging fluency and creativity through narrative writing. For students at the low-intermediate level, the Ministry competency statement specifically calls for fluency and focused attention on multiple verb tenses, especially past tenses in the oral component of the course. This course addresses these objectives head on.

- Communiquer en anglais avec une certaine aisance.

- Rédiger et réviser un texte — avec une attention plus particulière à quelques modals et à des temps de verbe parmi les suivants : simple present et present continuous, simple past et past continuous, present perfect, future.

- S’exprimer oralement — emploi généralement correct de verbes au passé; formulation de questions pertinentes en situation d’interaction.

Actively Engaged at College is different from what teachers are used to—but exactly what students need. Instead of essay writing, low intermediates using this book to master first-person narratives. Students work together in groups, collaborating to develop dramatic first-person stories. Each week, the just-in-time grammar and vocabulary lessons are exactly what they need for the next chapter in the story. Students want to look good in front of their peers and avoid looking bad, so each week students are motivated to impress each other as they workshop their stories.

The 7-week roommate narrative project

Students collaborate on a story about roommates. Each week, every member of their writing group writes a section of the story in the first person and from the perspective of one character in the story. They must submit their story using the FastAssignment Moodle plugin to check it for target structures, word count, and errors. Students can submit and revise as many drafts as they wish to get the score that they want. The teacher need only coach and encourage.

The project starts in week 4. Students get into groups and describe a house somewhere in the world. Each student invents an unusual character who lives in the house with the others. Each student will tell the story from the perspective of his or her fictional character. Since all of the characters live together and each of them is unusual, it doesn’t take long before they begin to cause problems for each other.

In week 5, students describe their own fictional character. The lesson focusses on descriptive vocabulary and routines using adverbs of frequency and present tenses. In groups, students take turns reading aloud what they wrote about the house. Once that’s done, they plan the next part of the story by answering questions. Making one student responsible for conducting the workshop ensures everything goes smoothly.

In week 6, there is a party planned for the new roommate. Students must decide who is the new roommate and then describe how each member of the house prepared for the party. This part of the story elicits the everyday vocabulary they learned related to cleaning and food preparation. Then, each student describes the events of the party, in which something goes terribly wrong.

In week 7, each character has a dream. The dream reveals a secret desire or fear. The first part of this section of the story relates the events in the dream using past tenses. The second part of this section includes an interpretation in present tenses.

In week 8, the house becomes overcrowded. Roommates bring home pets, relatives and lovers. This puts pressure on the other roommates leading to conflict. The obligatory context elicits past tenses and possessive forms. Instead of “the boyfriend of my roommate,” the grammar checker will suggest “my roommate’s boyfriend.”

In week 9, each character has a bad day. Students must write sentences with “when” or “while.”

When I arrived home, the house was a mess. While I was vacuuming the carpet, I knocked over the TV and broke it.

Sentences containing the target structures from lesson 9

In week 10, a meeting is called. The roommates hurl accusations at each other. Someone is punched and someone gets kissed. One of the roommates is asked to leave. Students use passive constructions to describe the upsetting events.

Final exams

Finals are easy. There are no multiple choice grammar exams. (The competency approach doesn’t allow it.) There is no final essay. (Essays can’t elicit the verb tenses from the course.) Students are simply told that the police came and want them to write a statement about what happened. This simple writing task elicits all of the grammar from the course.

The final oral is just as easy to explain. In pairs, ask and answer questions about your story with someone from a different writing group. Students sign up. The teacher listens in with a checklist containing all of the target structures from the course.

A course with personality

No other course book comes close to this. Why not? Part of the answer lies in the expectation that college courses should focus on academic research and debate. Actively Engaged at College does not. If that’s what teachers want, they should look elsewhere.

If they want a course focussed on practical skills and creativity that reliably produces the fluency and grammar skills described in the government objectives, this book is worth a try.

It just works so well. Students love it. Teachers trust the pedagogy. Download sample units of Actively Engaged at College.

Discussion

Why do so many 101 course books focus on just-in-case grammar lessons, newsy topics, argumentation, and speaking tasks that employ and elicit a very narrow range of verb tenses? Perhaps, these textbooks authors don’t know what we know:

A focus on news reports, controversy, and debate in low-intermediate ESL classrooms reduces interest-based motivation, isolating and silencing weaker students (Poupore, 2014). Some vocal students might engage, but just as many would rather not speak up on controversial issues.

In contrast, dramatic stories were found to have the strongest positive effect on interest-based motivation and group cohesion for everyone in the group. Narratives reliably engage more ESL students more of the time than current affairs stories and controversial topics.

A focus on academic writing does not help students with who can’t conjugate their verbs correctly. Academic English contains fewer verbs overall and fewer verb tenses with a much higher frequency of present tense verbs. How can students learn a wide range of verb tenses if the tenses never appear in the texts they read or in the texts they write?

In contrast, narratives have more verbs overall and more verb tenses. Not only do stories focus on events in time expressed with a range of tenses, the presence of quoted speech means all tenses are more likely to appear. Narratives have a much higher concentration of modals, simple present, present continuous, simple past, past continuous, present perfect, and future tenses (Biber et al., 1999). To elicit a range of verb tenses in authentic communication, we should teach and test non-fluent students with first-person narrative tasks.

Emphasizing academic English in courses for non-fluent learners reduces students’ integrative motivation when they find themselves in informal social situations (Segalowitz, 1976). In other words, teaching formal English to weaker students causes them to avoid contact with native speakers because everyday English doesn’t match the academic English they learned at school. Over time, avoidance stunts their fluency.

More meaningful engagement week after week through a collaborative narrative project produces fluency, motivation, and makes the grammar stick.